Marine heat wave caused key part of Florida’s coral reef to become “functionally extinct,” report says

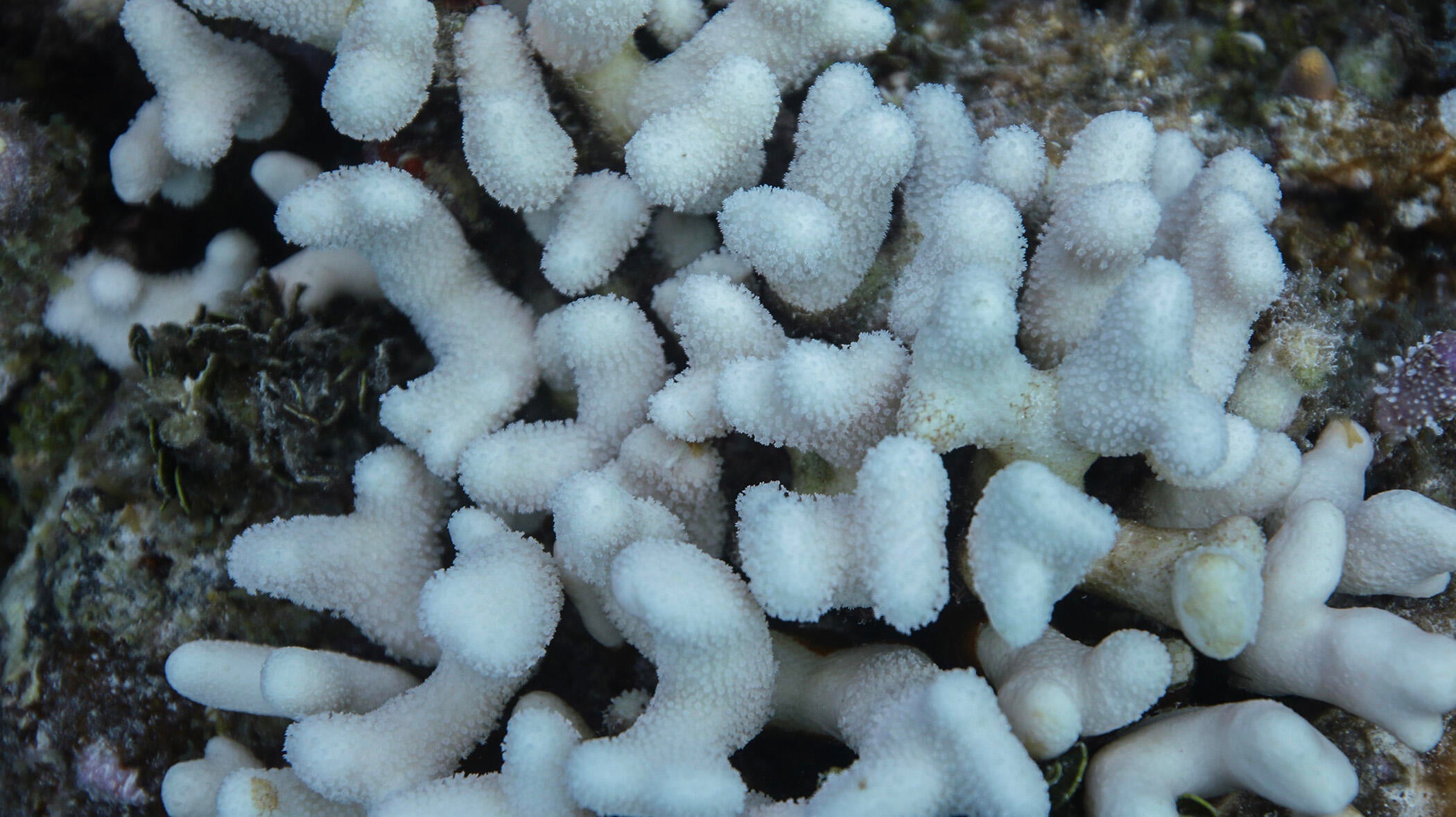

A record-setting marine heat wave stripped huge portions of Florida’s coral reef of their colors in 2023, triggering the ninth and worst mass bleaching event in the Caribbean. Temperatures soared for weeks, almost completely killing off two of the region’s oldest and most important coral species, according to a new report that aims to shine a light on how warming waters can be lethal for the ecosystems they’ve historically sustained.

Co-authored by scientists at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the University of South Florida and several nonprofit organizations, the report was published Thursday in the peer-reviewed academic journal Science. It shared striking findings from an investigation into the effects of that record heat wave on a 350-mile stretch of the Florida reef, which, researchers said, wilted as sea surface temperatures remained at or above 31 degrees Celsius — 87.8 degrees Fahrenheit — for an average of 40.7 days over the summer.

The heat stress in pockets of the reef during that time was as much as four times greater than it had been during any previous heat wave or any prior year that scientists recorded temperature data for the area, said Ross Cunning, one of the report’s lead authors and a biologist at the Chicago-based Shedd Aquarium, whose research centers around ways to make coral reefs more resilient against the effects of climate change.

Gavin Wright/Shedd Aquarium

Among the heat wave’s most devastating impacts were the deaths of two types of coral, staghorn and elkhorn, which are known as “reef builders” because they have provided the structural foundation from which Caribbean reef ecosystems can grow for thousands of years. According to the report, between 97.8% and 100% of coral belonging to those two species perished in the heat wave, marking what researchers characterized as “their functional extinction from the region.”

“Functional extinction” means there is no longer enough of either coral species in the Caribbean in order for staghorn or elkhorn to continue performing their longstanding services to the reef at large.

“These corals are the ecosystem engineers of reefs,” Cunning told CBS News. “They literally build the three-dimensional framework that we know as the coral reef.”

Cunning likened the “huge losses” felt by the Caribbean reef in their absence to those a diverse forest might suffer after losing its largest and most vital trees: “What you’re left with is a range of smaller trees and shrubs and other plants, and they’ll continue to grow and form together some type of forest,” he said, “but it’s a forest transformed without these major contributors.”

The 2023 heat wave in Florida’s reef has been described as a bleaching event, when corals purge their colorful algae and appear white and brittle in response to warming oceans. Bleaching robs coral of nutrition and makes them more susceptible to disease, which kills them over the long term. But the circumstances in this case were so severe that they actually accelerated that process in some of the affected reefs, said John Parkinson, a professor at the University of South Florida who specializes in marine ecology and is another co-author of the new report.

Shedd Aquarium

“Coral bleaching is definitely a problem, but some of these corals didn’t even get a chance to bleach,” Parkinson told CBS News. “They actually just started melting. Essentially, they were sloughing their tissue.”

Damages felt in the wake of the 2023 heat wave are most likely permanent, researchers said. A stark example of the warning call from climate scientists at the University of Exeter’s Global Systems Institute in England, who earlier this month released a report of their own that found coral reefs had become the first environmental system on Earth to pass a climate “tipping point,” as global warming has increased ocean temperatures around the world.

Around 25% of all marine life depend on coral reefs for protection and habitats, while the Global Systems Institute estimated that reefs provide crucial support for about 1 billion jobs. Climate scientists have also noted how reefs, in Florida and elsewhere, help shield coastlines and the communities that populate them from things like storm surge, flooding and erosion.

Gavin Wright/Shedd Aquarium

Scientists expect heat waves to become more intense and more common without stronger efforts to reduce the prevalence of fossil fuels and the greenhouse gas emissions that linger in the atmosphere after burning them. In their new report in Science, the co-authors wrote, “the frequency and severity of extreme climate and weather events, including marine heat waves, are increasing, resulting in widespread degradation of the function, structure, resilience, and adaptive capacity of ecosystems.”

Those aren’t reasons to lose hope for a brighter future, they said. While Parkinson referred to the record heat wave as “devastating” and “off the charts,” he also told CBS News that he likes to remain optimistic about the possibility that things will change for the better.

“You know, some corals survived, and the people who are involved in restoration are still going at it, and we’re still trying to keep corals around,” he said. “We all believe that we can, but we really need help from the people who have the power to adjust our approach to these climate policies.”